The Third Phase: Mass Mobilisations & Moratoriums 1969-72

In the three years following the 1966 election, the cumulative impact of the widening circles of civil disobedience and nonviolent direct action, coupled with the daily horrific images from the war itself, led to concerned people across Australia reassessing their thinking about the war. By mid-1969, opinion polls indicated that the previous 1965-66 majority in favour of Australian troops going to Vietnam had changed to a clear majority, 55%, now wanting to see them brought home (compared to 40% wanting them to stay in Vietnam).[27]

This second phase of unprecedented levels of civil disobedience on the part of antiwar communities and constituencies across the country served to pave the way for an equally extraordinary third phase of mass mobilization across the whole country. This took the shape of the Vietnam Moratorium movement, which launched two major Moratoriums actions in May and September 1970, and a third in June 1971. Within two years, this mass mobilization was to contribute importantly to a Labour victory at the 1972 Election on an election platform of ending conscription and Australian participation in the Vietnam War.

The first May 1970 Moratorium

The first of the mass mobilizations took place in May 1970 in cities and towns across Australia. Led nationally by Chairperson, Jim Cairns, and by Vice-chairpersons, Laurie Carmichael (Amalgamated Engineering Union), Jean McLean (SOS and ALP), and Harry Van Moorst (students’ representative), the Moratorium movement was an all too rare moment when a coalition of peace, student, academic, union, professional, local community groups, and sympathetic sections of the ALP, had a major impact on national policies on war, peace, conscription and Australians attitudes to Asia.

A February 1970 discussion paper by Ken McLeod, one of the Sydney Moratorium organizers, circulated ahead of the May 1970 Moratorium, indicates the thinking that led to the new antiwar mobilization strategy:

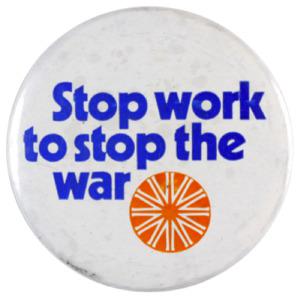

Only a mobilization of tens of thousands…could be regarded as successful in terms of political pressure to withdraw the troops and repeal the National Service Act…The Vietnam Moratorium Campaign must be unmistakably the biggest manifestation of anti-war feeling ever seen in this country. Measured against the suffering and endurance of the Vietnamese people, morality indeed demands no less…the Moratorium Campaign affords an excellent opportunity to experiment with and develop new patterns of activity…The recent actions of the Committee in Defiance, the whole stance of draft resistance…have pointed in new and positive direction…the whole theme of the Moratorium, ‘A Moratorium Against Business as Usual’ [declares] our intention to shut down our factories, to occupy our universities and classrooms, to interrupt our daily patterns of suburban routine, and to directly challenge the government to withdraw our troops and end conscription.[28]

As part of the “no business as usual” principle, reflecting the moral urgency of action, the Melbourne Moratorium took place on a working day, Friday May 8th 1970, with people asked to come from their work or study places. It involved some 100,000 people in Melbourne and 200,000 across the country, far in excess of what even organizers like Ken McLeod were expecting, and despite Premier Bolte and the tabloid press predicting that that it would lead to violence.

In Melbourne, more than 1 in 30 Melbournians took part in a nonviolent sit-in of people from the Parliament end of Bourke St to William St at the other end. In Sydney, there was a similar sit-in outside the Town Hall.

Key features of the Vietnam Moratoriums

The Moratorium mobilization and form of organization involved an astonishingly extensive range of local community groups (20 in Melbourne), student groups, faith communities, unions, professional groups, Labour party parliamentarians and branches, and other political parties and groups.[29] This network built upon but reached well beyond the antinuclear networks of the early 1960s.

Organizationally, the Moratorium structures involved very democratic forums for planning and organizing the Moratorium actions through town hall meetings of affiliated groups. Particularly in evidence was the genuine willingness of various groups with very different ideas, political stances, and beliefs - from militant left to more moderate right groupings - to cooperate and work together despite all their differences. This was probably due to participants feelings of an overriding moral urgency to act to save lives, both amongst the Vietnamese and Australian conscripts and forces. While some historians of the period have tended to invoke the “left flank” theory of why so many people were prepared to be involved in mass direct action in the form of the Moratorium mass sit-downs and occupations of city centres, a more plausible interpretation, associated with the theme of “stopping business as usual”, was the success of the wave of nonviolent civil disobedience antiwar actions from 1968 onwards in encouraging people to think about the urgency of personally taking action to stop the ongoing slaughter and horror of the war.

The Moratoriums were highly successful in achieving major media breakthroughs in coverage and communication of anti-war anti-conscription arguments and messages in a context where almost all the mainstream media had been hostile to the peace movement. The noted observer of Australian society and culture, Donald Horne (a supporter of the war at the time), wrote later: “In Sydney there was a sight that many of those present expected to remember for the rest of their lives, a peaceful crowd of 25,000 sitting down in front of Sydney Town Hall. In Melbourne, there were scenes far beyond any radical hopes – a crowd of somewhere between 80,000 and 100,000 sitting in the street and chanting,’We want Peace’.”[30]